Over 100 million adults (42.4%) are obese in America. Obesity comes with substantial health risks & impacts on quality of life as well as mental health. As such, nearly half of adults in the US attempt weight loss on a yearly basis but the number of people who are successful in losing weight and successfully maintaining that weight loss are extremely low. Moreover, the amount of misinformation surrounding fat loss is overwhelming. In this podcast, Dr. Norton breaks down the most important things to consider for a successful weight loss lifestyle program to have success and maintain it for the long term.

The confusion around fat loss

- Hundreds of thousands if not millions of posts about weight loss are made yearly on social media

- Research shows that it is star power, not science that drives decision making amongst weight loss content consumers. 1

- This has led to widespread confusion amongst what actually matters for weight loss

The problem with weight loss?

- Weight loss is not the problem.

- The vast majority of people who lose weight do not maintain the weight loss & put most or all of it back on. 2 Many even add more weight that they originally began with. 3

- This is driven by a biological drive to return to pre-diet weight through decreases in energy expenditure from reduced REE, NEAT, and physical activity. It is also perhaps more driven by increases in appetite and decreased satiety. 4 5

What matters based on the evidence

- The most important factor? Adherence to a calorie deficit

- Amongst popular diets, there are no differences in weight loss in the long term, but when subjects are stratified based on adherence regardless of diet type, there is a linear effect of adherence on weight loss success. 6 7 8

- How to improve adherence?

- Self efficacy 9

- Social support

- Social identification with a dietary approach 10

- Greater initial weight loss 11 12

- Tailoring diet to the individual’s preference 13 14

- Increase protein intake 15

- Self monitoring through weighing and logging food/calories 16

- Establishing a caloric deficit

- Despite social media claims, a caloric deficit produces weight loss regardless of method used to establish the deficit. 17 18

- Some social media ‘experts’ have claimed that fat cannot be lost when insulin is elevated even during a caloric deficit, but this is not supported by research data.

- Diets equal in calories & protein but differ in carbohydrates and fats produce similar fat loss even with significantly different insulin levels 19 20 21

- GLP-1/GIP mimetics significantly increase meal insulin responses but cause massive weight loss. 22 23

- Even a diet based almost exclusively on sugar can produce massive weight loss when it induces a substantial caloric deficit. 24

- While insulin can inhibit lipolysis and fat oxidation, fat oxidation is not the same thing as fat loss. As high fat, low carb diets increase fat oxidation but also increase fat storage while low fat, high carb diets decrease fat oxidation but decrease fat storage since less than 2% of dietary carbohydrate is stored in fat tissue. 25

- Some people claim that they ate in a calorie deficit and did not lose weight but they do not understand what a caloric deficit is

- What is a calorie deficit?

- Expending more calories than you consume

- What is a calorie: a unit of measurement of the energy stored in the chemical bonds of food molecules. Calories = energy and the two terms are interchangeable

- This energy is captured for use to drive chemical reactions in the body, mostly through the production of ATP, a high energy phosphate. The liberation of ATP to ADP + Pi is an energetically favorable reaction that can power other reactions in the body

- If you consume more energy than you expend, you gain weight as the excess energy is stored as triacylglyceride in adipose tissue. If you expend more energy than you consume, your body must rely on it’s own energy stores & derives them through the liberation of TAGs from adipose tissue to make up the energy deficit & produce ATP

- Energy balance = Energy in vs. Energy out

- Energy in = calories consumed – non-metabolizable calories.

- Energy out = Total energy expenditure (TEE) = Resting energy expenditure (REE) + Thermic Effect of Food (TEF) + Physical Activity (PA)

- Physical Activity (PA) = Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) + Exercise Activity (EA)

- So overall Energy Out = REE + TEF + NEAT + EA

- REE = energy expended at rest & is approximately 50-70% of TEE for most people

- TEF = energy required to extract energy out of food

- NEAT = unconscious body movements such as postural energy, pacing, fidgeting, & other unintentional movements

- EA = purposeful movement

- TEE is modifiable through changes in REE & NEAT. During overfeeding both REE & NEAT increase & both decrease during a calorie deficit. 26 27 28

- TEE is NOT a set number but rather a moving target & the amount that it changes in response to overfeeding or underfeeding can vary by quite a bit between individuals. 29

- It is thought that people who are obese resistant have better appetite regulation & also tend to spontaneously increase their NEAT during overfeeding to compensate for increased energy intake. 29 30

- Why do people believe calorie deficits don’t work?

- Since TEE is adaptable, people are often confused because they may use an online calculator which estimates a calorie deficit for them, but when they consume those amounts of calories they don’t lose weight. This doesn’t mean calorie deficits don’t’ work, it simply means that amount of calories is not a deficit for them, or they are making tracking errors

- Tracking errors are the biggest source of confusion. Research has demonstrated that people who claim they can’t lose weight on low calories actually underreport their caloric intake by over 50% & overreport their physical activity by nearly 50%. 31

- Devices such as wrist worn watches that estimate ‘calories burned’ also tend to drastically overestimate energy expenditure. 32

- People also tend to weigh in sporadically and don’t understand how weight fluctuations work

- People claim hormones can cause violations of the laws of energy balance, but any hormonal shifts that impact weight loss or gain do so through either modifying energy intake or expenditure. For example hypothyroidism causes a decrease in REE. 33

- Energy balance does capture all explanations for weight gain or loss which is why patients who are examined under strict metabolic ward conditions where food intake is controlled, very consistently lose weight. 34

Exercise

- Exercise can increase energy expenditure, but the increase in energy expenditure tends to be partially compensated for by decreases in other areas of energy expenditure such as NEAT & REE. 35 36That said, exercise appears to produce a ‘net’ calorie burn of approximately 72 kcal per 100 kcal burned from EA. 37This may at least partially explain why weight loss from exercise is often less than is predicted based on the energy expended during the activity. 38

- While exercise can increase TEE, it also appears to have a powerful effect on appetite regulation. Exercise appears to increase brain sensitivity to satiety signals. 39 40 41

- Exercise also appears to be one of the only modalities that can change body fat set point to a lower level than previous. 42

- In accordance, people who successfully lose weight and maintain their long term weight loss are much more likely to engage in regular exercise (over 85% of successful weight loss maintainers) compared to those who don’t. 43

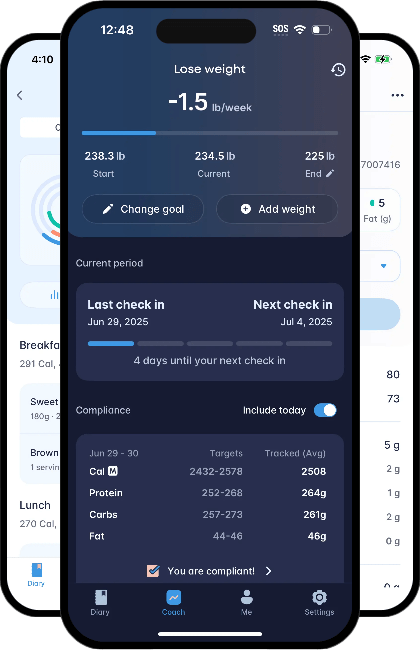

Self Monitoring

- A very consistent characteristic of successful weight loss maintainers is that they practice regular self monitoring 44

- This can be weighing themselves, tracking their food, weighing their food, or any form of self monitoring

- People who practice self monitoring are much more likely to lose weight and keep it off compared to those who don’t do it. 45

- Self monitoring alone appears to cause behavior change, with the simple act of frequent self-weighing resulting in weight loss amongst obese individuals. 46

- “That which gets measured gets managed”

Do macronutrients matter?

- The caloric deficit is the most important thing to create weight loss. But the composition of the calorie deficit appears to matter

- Protein

- Protein appears to have a greater TEF response (20-30% of energy consumed) than carbohydrates (5-10%) or fats (0-3%). 47

- High protein diets (>1.6g/kg BW) appear to lead to better retention of lean mass than moderate or low protein diets. 48

- High protein diets may produce better satiety but the effect isn’t always consistent and likely depends on the specific source of protein. 49 50

- Carbohydrate intake vs. fat intake does not appear to affect fat loss in controlled human feeding trials where calories & protein are equated. 20

- The type of carbohydrate likely matters however, as high fiber diets have been demonstrated to improve fullness, satiety, and decrease spontaneous calorie intake. 51 52

- This is why I recommend when developing a diet to first focus on an appropriate amount of calories to create the calorie deficit you need. Then determine your protein intake based on your body weight or lean mass. Then allot your remaining calories to carbohydrates and fats based on your dietary preferences while making sure that you consume sufficient dietary fiber (at least 15g fiber/1000 kcal dietary intake).

Sleep

- Sufficient sleep improves appetite regulation while sleep deprivation spontaneously increases caloric intake.

- This may be explained by changes in hunger hormone secretion in response to insufficient sleep. 53

- Sleep restriction of ⅔ of normal sleep for 8 days can increase caloric intake by over 500 kcal per day. 54

- This increase in calories appears to be from increased snacking. 55

- Sleep restriction can also change the composition of weight loss, with people who are sleep restricted losing less fat and more lean mass than those who get enough sleep. 56 57

Supplements

- Supplements play little to no role in long term fat loss. There are a few that have a small impact but it is VERY small compared to nutrition and exercise and only consistent with a few supplements

- Ephedra use appears to results in ~1kg body weight loss but may have adverse side effects. 58

- Creatine supplementation appears to reduce body fat by ~0.5% 59

- Melatonin supplementation appears to reduce body fat by approximately ~0.5% 60

References

- Whose tweets about obesity and weight loss gain the most attention: celebrities, political, or medical authorities?

- Long-term weight loss maintenance in the United States

- [The mediocre results of dieting]

- Biology’s response to dieting: the impetus for weight regain

- How dieting makes some fatter: from a perspective of human body composition autoregulation

- Comparison of dietary macronutrient patterns of 14 popular named dietary programmes for weight and cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised trials

- Dietary adherence and weight loss success among overweight women: results from the A TO Z weight loss study

- Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial

- “An Important Part of Who I am”: The Predictors of Dietary Adherence among Weight-Loss, Vegetarian, Vegan, Paleo, and Gluten-Free Dietary Groups

- “An Important Part of Who I am”: The Predictors of Dietary Adherence among Weight-Loss, Vegetarian, Vegan, Paleo, and Gluten-Free Dietary Groups

- Lessons from obesity management programmes: greater initial weight loss improves long-term maintenance

- Weight change in the first 2 months of a lifestyle intervention predicts weight changes 8 years later

- Adherence to the Mediterranean diet, long-term weight change, and incident overweight or obesity: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort

- Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates

- Dietary protein – its role in satiety, energetics, weight loss and health

- Self-monitoring in weight loss: a systematic review of the literature

- Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial

- Obesity Energetics: Body Weight Regulation and the Effects of Diet Composition

- Effect of Low-Fat vs Low-Carbohydrate Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss in Overweight Adults and the Association With Genotype Pattern or Insulin Secretion: The DIETFITS Randomized Clinical Trial

- Obesity Energetics: Body Weight Regulation and the Effects of Diet Composition

- Energy expenditure and body composition changes after an isocaloric ketogenic diet in overweight and obese men

- Effects of subcutaneous tirzepatide versus placebo or semaglutide on pancreatic islet function and insulin sensitivity in adults with type 2 diabetes: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-arm, phase 1 clinical trial

- Tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor co-agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes with unmatched effectiveness regrading glycaemic control and body weight reduction

- Treatment of massive obesity with rice/reduction diet program. An analysis of 106 patients with at least a 45-kg weight loss

- Effect of carbohydrate overfeeding on whole body macronutrient metabolism and expression of lipogenic enzymes in adipose tissue of lean and overweight humans

- Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis in Human Energy Homeostasis

- Some metabolic effects of overeating in man

- Effect of calorie restriction on resting metabolic rate and spontaneous physical activity

- Resistance to weight gain during overfeeding: a NEAT explanation

- Resistance and susceptibility to weight gain: individual variability in response to a high-fat diet

- Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects

- Accuracy and Acceptability of Wrist-Wearable Activity-Tracking Devices: Systematic Review of the Literature

- Resting energy expenditure is sensitive to small dose changes in patients on chronic thyroid hormone replacement

- Weight loss in 108 obese women on a diet supplying 800 kcal/d for 21 d

- Physical activity and energy balance

- Constrained Total Energy Expenditure and Metabolic Adaptation to Physical Activity in Adult Humans

- Energy compensation and adiposity in humans

- Why do individuals not lose more weight from an exercise intervention at a defined dose? An energy balance analysis

- Effects of exercise intensity on plasma concentrations of appetite-regulating hormones: Potential mechanisms

- Acute and Chronic Effects of Exercise on Appetite, Energy Intake, and Appetite-Related Hormones: The Modulating Effect of Adiposity, Sex, and Habitual Physical Activity

- Effects of Aerobic, Strength or Combined Exercise on Perceived Appetite and Appetite-Related Hormones in Inactive Middle-Aged Men

- Regular exercise attenuates the metabolic drive to regain weight after long-term weight loss

- Successful weight loss maintenance: A systematic review of weight control registries

- Consistent self-monitoring of weight: a key component of successful weight loss maintenance

- Dietary self-monitoring and long-term success with weight management

- Self-weighing promotes weight loss for obese adults

- Diet-induced thermogenesis in man: thermic effects of single proteins, carbohydrates and fats depending on their energy amount

- Dietary protein and exercise have additive effects on body composition during weight loss in adult women

- Higher protein intake preserves lean mass and satiety with weight loss in pre-obese and obese women

- Effect of short- and long-term protein consumption on appetite and appetite-regulating gastrointestinal hormones, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Effect of a plant-based, low-fat diet versus an animal-based, ketogenic diet on ad libitum energy intake

- Short-Term Effect of Additional Daily Dietary Fibre Intake on Appetite, Satiety, Gastrointestinal Comfort, Acceptability, and Feasibility

- Associations of short sleep duration with appetite-regulating hormones and adipokines: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Effects of experimental sleep restriction on caloric intake and activity energy expenditure

- Sleep curtailment is accompanied by increased intake of calories from snacks

- Influence of sleep restriction on weight loss outcomes associated with caloric restriction

- Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity

- Dietary supplements for body-weight reduction: a systematic review

- Changes in Fat Mass Following Creatine Supplementation and Resistance Training in Adults ≥50 Years of Age: A Meta-Analysis

- Melatonin supplementation and anthropometric indicators of obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis