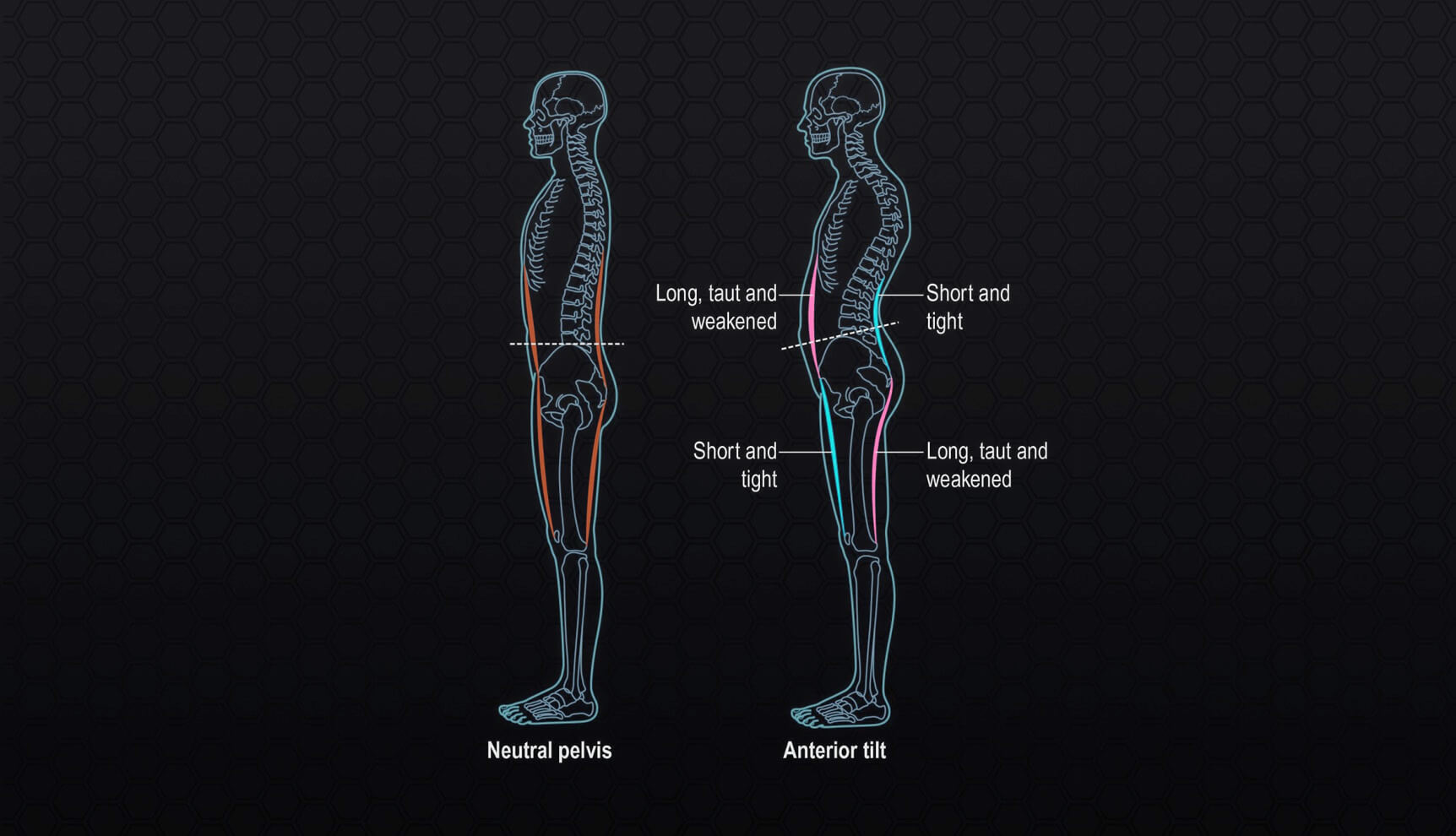

If someone were to tell you your butt looks like Donald Duck’s, then you likely have anterior pelvic tilt. The reason for looking like Donald Duck is because the front of your pelvis points down, and the back of it rises up and creates that hyper-lordotic spinal curve you see on Instagram so often. Not only that, but if you have excessive anterior pelvic tilting, it can affect your posture and make you look like you have a huge gut.

However, this isn’t to say that anterior tilting of the pelvis is necessarily a bad thing. Tilting is a natural function of your pelvis. In fact, your pelvis can:

- laterally tilt to the left or right

- posteriorly tilt (think Michael Jackson when he grabs his junk) or

- anteriorly tilt like Donald Duck

In terms of human movement, these functions are integral. And while a large body of research basically reduces a high degree of anterior tilt to not having tight hamstrings and a lack of correlation to lower back pain, it’s still safe to think about compensatory patterns that can develop due to a lack of function in the area.

To elaborate, since the research doesn’t denote a clear causality—a “this” yields anterior pelvic tilt situation—we can theorize and contemplate a lot of variables. In fact, Russell states “There are many Internet sites that support the belief that high-heeled shoes cause increased lordosis. However, published research for this topic mostly does not support this belief; but some mixed results, small subject groups, and questionable methods have left the issue unclear.”

And if you simply look at the posture of people who wear high heels, it’s a good hypothesis worthy of more research. But there are some established research areas we can look at to inform our training.

Commonalities

Low back pain and anterior pelvic tilt are common. Go to Starbucks and look at how

people walk. You can see it. And it doesn’t matter the shoes they wear. Running shoes, heels, flats, whatever. Something got them to where they currently are and that’s a good starting point, in lieu of worrying about the time before the dysfunction.

So I’ve touched on it briefly, but for people who have lower back pain, the research I cited in my core endurance piece noted that targeted core work can help alleviate pain in the lower back. Research cited below notes that abdominal training (not the entire core) doesn’t really help that much with anterior pelvic tilt.

And while the tilt and the pain may or may not be related, nevertheless, we have exercises at our disposal to fix two problematic areas at once. Since I defined the core as your butt and abs (your torso and pelvis), each of those exercises recruits them and strengthens them. With that in mind, you have a good starting point to feel your positioning in your lifting.

The cues

So in the video above, you’ll see two deadlift forms. The first one is pretty common in brand new, untrained clients. What’s wrong with the picture? At the lockout, there’s no support and you’re struggling to keep the weight up.

In the second form, you see better supporting alignment and if your grip strength holds, you can hang out it in that position for a while due to the support of your musculoskeletal system.

To go from point A to the better position of point B, I use two cues, oftentimes one followed by the other. The first one is to jam your head into the ceiling. Obviously, most people are tall enough to where they can’t do this, so the end result is that she stands taller. Sometimes, this results in better alignment and fixes a lot of the problems. Other times, it results in the same exact form, only they’re halfway between their original point A and the optimal point B.

When that happens, the second cue is to squeeze their glutes. Combined with the first cue, this helps them to stand taller, and take their pelvis out of the anterior pelvic tilt they started and ended with. Given that anterior tilting is so common for a new trainee, having her squeeze her glutes usually puts her pelvis in a more optimal neutral position at the lockout, which is the goal.

I start with the deadlift in this instance because it’s less technical than a squat or any other unilateral movement, but when a trainee has the technical acumen, she can apply the cues to these other movements as well.

Glute Bridge

Depending on the rate of the learning curve, the glute bridge is another good exercise to train the posterior tilting position. In fact, to feel the glutes work hard, you have to keep that posterior tilt throughout for it to even be effective. And while I didn’t get a video, a band around the knees will let you know if you’re doing it properly. Hint: you’ll feel it deeply in your glute medius if you’re doing it right.

And when you become proficient at the two leg version of the glute bridge, try a single leg variation. The best part about the single leg version is that you can quickly detect any unilateral weakness you might have, and subsequently fix it.

Conclusion

I stress this often, but it beats repeating. The best way to adapt, even when it comes to your posture, is to put in the reps. Furthermore, how you look depends on how you move. Training posterior tilting patterns isn’t teaching you another bad habit—exceptions apply, but if you’re a person who has a gnarly anterior tilt, you’ll be fine—but simply adding more movement. And you need to be able to perform both well so you can move properly when you lift, and when you live life. For instance, if you can’t control the ability to tilt your pelvis forward, and then back, it will make deadlifting a real hassle. Hinging to touch the bar requires you tilt your pelvis forward, after all. And then you move out of that position. And the same applies for a squat.

Furthermore, a good portion of exercises you perform in the gym require you to be in some degree of hip flexion. And that also means you’ll have to tilt your pelvis anteriorly. Exercises like bent over rows, rear delt flies, and so forth. So it’s imperative to be able to move in and out of these positions.

References

- Russell, B. S. (2010). The effect of high-heeled shoes on lumbar lordosis: a narrative review and discussion of the disconnect between Internet content and peer-reviewed literature. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine,9(4), 166-173. doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2010.07.003

- Reis, F. J., & Macedo, A. R. (2015). Influence of Hamstring Tightness in Pelvic, Lumbar and Trunk Range of Motion in Low Back Pain and Asymptomatic Volunteers during Forward Bending. Asian Spine Journal,9(4), 535. doi:10.4184/asj.2015.9.4.535

- Levine, D., Walker, J. R., & Tillman, L. J. (1997). The effect of abdominal muscle strengthening on pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice,13(3), 217-226. doi:10.3109/09593989709036465

- Pelvic tilt. (2016, December 04). Retrieved September 26, 2017, from https://www.strengthandconditioningresearch.com/biomechanics/pelvic-tilt/