If you haven’t noticed by now, people really like to perform the back squat, bench press, and deadlift. So much so that powerlifting has reached an all-time high in popularity and participation. The sport has certainly evolved into an amazing feat of strength as competitors continue to push the envelope of what we thought was possible. Just as the sport has evolved, so too have the training strategies that are used to get as strong as possible. One such evolution that has caught on as of late is the use of accommodating resistance in training. You may have seen those colorful bands and/or chains looped around the bar as people squat at your gym or on your Instagram feed. Although the use of bands and chains has only recently become mainstream, it isn’t a new concept. You may have heard of people like Louie Simmons or Dave Tate who were pioneers in the world of powerlifting. These two, along with many other successful powerlifters, have been using accommodating resistance in training long before you may have even heard of powerlifting. But just how beneficial can accommodating resistance be in your training? Well, the research is clear that accommodating resistance has some major benefits. But knowing how to use it practically is an important piece of the puzzle if you want to see results. So let’s explore the world of accommodating resistance so you can start applying it to your own training!

Benefits of Accommodating Resistance

When it comes to putting in work in the gym, we are all just looking to get bigger, stronger, and faster. Not a lot of research has investigated the hypertrophy implications of accommodating resistance, so it is tough to say whether an advantage exists in this realm. Certainly a case can be made from an exercise variety and tension standpoint, but we will touch on that more later on. The area where accommodating resistance seems to really shine would be the stronger and faster aspect of training.

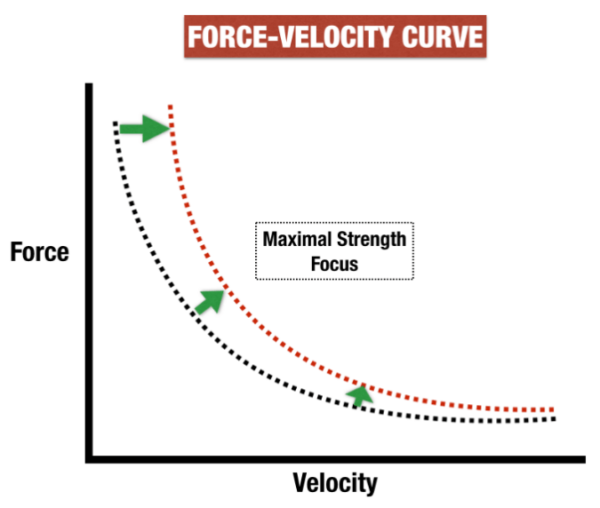

If you are not familiar, the action of our muscles is dictated by a force-velocity relationship or curve [7]. On one end of the curve you have max velocity movements such as sprinting, bounding, or countermovement jumps. Shift to the other side, and you have maximum force movements such as a back squat or deadlift one repetition max attempt. Generally speaking, the faster the movement, the less force is required and vice versa. This is why a true 1-rep max takes so long to complete compared to a max vertical jump.

However, those slow grinding reps can sometime be missed because of a lack of speed. If you take too long to lift the weight, your muscles will fatigue under the load and you’ll lose force production. A good strategy to combat this in training is to try and shift the force velocity curve to the right such that greater speed is achieved at any given force production. If you are able to generate more speed while producing the same or more force, you have a much greater chance of completing those max effort lifts.

Accommodating resistance effectively changes the kinetics and kinematics of a given lift in a way that promotes this shift of the force velocity curve [3][5]. Essentially, adding bands or chains to say, a back squat, makes for greater force production and muscle activation in the late stage of the concentric action, as well as the early stage of eccentric action. In other words, it overloads the top of the squat. During a normal squat, you may be letting off the gas a bit at the top end of the squat. However, with band resistance, you must continue to accelerate throughout the whole range of motion. This makes for a more challenging exercise compared to that of traditional resistance training.

Several studies have shown that accommodating resistance is significantly more effective in augmenting speed and power compared to traditional resistance training [1][6][9]. This is true both for chronic adaptions to those characteristics as well as acute improvement, as it has been shown to improve sprint performance via post activation potentiation [10]. Additionally, many studies have shown that the use of accommodating resistance leads to significant strength improvements [4][8]. In fact, several have shown it to be superior for improving strength compared to traditional resistance training [1][2]. With these results, it is clear to see that accommodating resistance is something you should consider adding to your training arsenal.

How to Use it In Your Training

You’ll find there are two different ways people advocate using bands or chains in training. The Conjugate Method of training, which has popularized accommodating resistance, splits exercise into dynamic effort and max effort. More often than not, you’ll see people using accommodating resistance on dynamic effort days. These are lighter days which focus on speed so it makes sense to use a modality that improves speed and power production. The bands will add tension to the end range of motion of a given lift which forces the lifter to continue accelerating hard throughout the movement. So the implications for speed-strength activities is well justified.

However, for max effort lifts, the rationale becomes a bit murky. When using bands for any lift, we know that the middle and top end of the motion are overloaded, but this also means that the bottom of the lift is easier in comparison. For example, you may put 315 pounds on the bar and add band resistance to make it feel like 405 pounds at the top. While 405 may be difficult to lock out, perhaps 315 is relatively easy to get out of the hole with. This works very well for those who compete in “geared” powerlifting, where lifting suits provide assistance in the bottom of a given lift. At the same time, many feel this is not a good strategy for people who compete in raw powerlifting. The feeling here is that you’ll train yourself to be weak in the bottom of a lift which will ultimately limit you from getting stronger.

While this logic is sound, it is worth investigating the truth in these claims. The studies cited above used band tension to make up 25% of the overall load. That means the weight on the bar was up to 25% lighter at the bottom compared to the top. Despite this, the subjects did not seem to develop any weakness in the bottom portion of the lift and improved overall strength as much or more than those in the traditional group. So it seems there is something about overloading the muscles that seems to translate into improved strength throughout the whole lift.

It is likely that combining accommodating resistance with traditional resistance training is the best way to go. This allows you to train and overload different portions of the lift which leads to more efficient strength adaptations. For example, you could alternate heavy squat sessions by using accommodating resistance in one and straight weight in the other. One popular method of overloading is to use the band tension in reverse. This allows you to add more weight on the bar as the bands give assistance in the bottom of the lift. This could be especially helpful for raw lifters as it give you the feeling of holding actual weight in the top portion of the lift. This is a much different feeling compare to elastic tension and could help with sport specificity.

With all the ways bands and chains can be used, it can be confusing to pick the right one for you. Here is a list of how you might use accommodating resistance in your training:

- Use band tension to force constant acceleration during speed/dynamic effort days

- Use bands/chains to overload the middle and top portion of a given lift

- Use reverse band tension to simulate a heavy raw squat while relieving tension in the bottom of the lift

- Use band/chains to ease the pressure on joint in the bottom of a lift while still stimulating higher order motor units (This is useful for those who have nagging injuries that are aggravated by heavy, full range movements)

- Use bands on higher repetition sets in order to provide a novel stimulus for hypertrophy

- Use accommodating resistance just to spice up your training and try something new

Conclusion

There is no doubt that accommodating resistance represents a legitimate training modality that will lead to gains in strength when used correctly. Its bad reputation among raw powerlifters is probably due to their misunderstanding of how it can be useful. It is important to remember that squatting with bands is not the same as squatting with free weight, and that is the point exactly. You are trying to provide a novel stimulus and manipulate the force-velocity curve in order to make the free weight squat easier to perform. The research is clear in terms of how useful it can be for improving strength and power, but the key is figuring out the right balance of accommodating resistance and traditional free weight training to bring out the most efficient adaptions in your training. Once you do that, you will definitely reap the rewards in the gym or on the platform.

References

- Anderson CE, Sforzo GA, Sigg JA. The effects of combining elastic and free weight resistance on strength and power in athletes. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2008 Mar 1;22(2):567-74.

- Burnham TR, Ruud JD, McGowan R. Bench press training program with attached chains for female volleyball and basketball athletes. Perceptual and motor skills. 2010 Feb;110(1):61-8.

- Galpin AJ, Malyszek KK, Davis KA, Record SM, Brown LE, Coburn JW, Harmon RA, Steele JM, Manolovitz AD. Acute effects of elastic bands on kinetic characteristics during the deadlift at moderate and heavy loads. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2015 Dec 1;29(12):3271-8.

- Ghigiarelli JJ, Nagle EF, Gross FL, Robertson RJ, Irrgang JJ, Myslinski T. The effects of a 7-week heavy elastic band and weight chain program on upper-body strength and upper-body power in a sample of division 1-AA football players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2009 May 1;23(3):756-64.

- Israetel MA, McBride JM, Nuzzo JL, Skinner JW, Dayne AM. Kinetic and kinematic differences between squats performed with and without elastic bands. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2010 Jan 1;24(1):190-4.

- Joy JM, Lowery RP, de Souza EO, Wilson JM. Elastic bands as a component of periodized resistance training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2016 Aug 1;30(8):2100-6.

- Komi PV. Measurement of the force-velocity relationship in human muscle under concentric and eccentric contractions. InBiomechanics III 1973 (Vol. 8, pp. 224-229). Karger Publishers.

- Rhea MR, Kenn JG, Dermody BM. Alterations in speed of squat movement and the use of accommodated resistance among college athletes training for power. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2009 Dec 1;23(9):2645-50.

- Wallace BJ, Winchester JB, McGuigan MR. Effects of elastic bands on force and power characteristics during the back squat exercise. Journal of strength and conditioning research. 2006 May 1;20(2):268.

- Wyland TP, Van Dorin JD, Reyes GF. Postactivation potentation effects from accommodating resistance combined with heavy back squats on short sprint performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2015 Nov 1;29(11):3115-23.