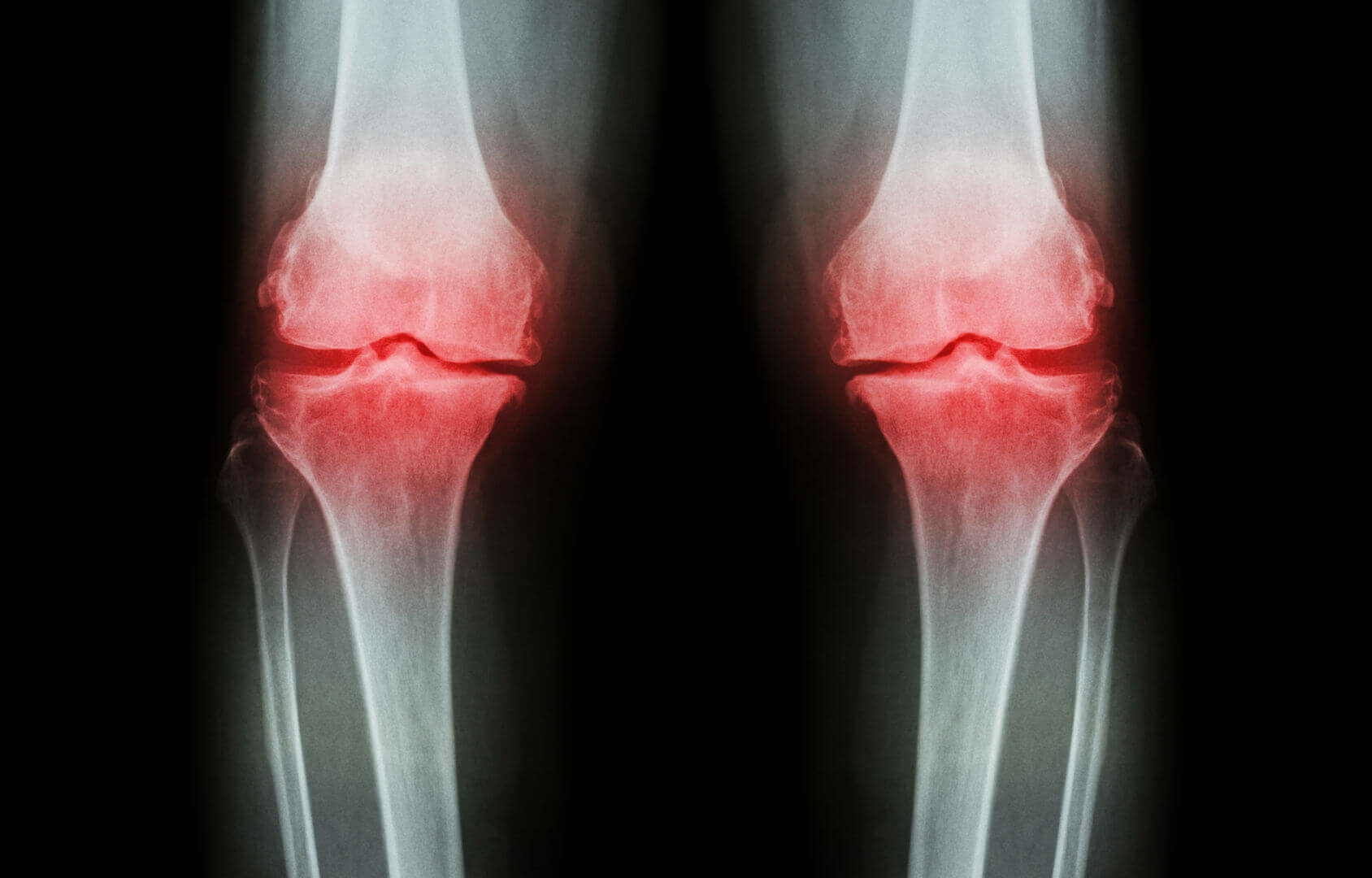

In powerlifting, knee injuries are among the common injuries you will see. My goal for you, if you lift heavy, is to make this less common. While we always ensure we’re using proper form, sometimes we do things outside of training that might place undue stress on our knee joint. Still, while training a rep might not be as clean as we would like it to be and it could cause injury or pain. If we prepare ourselves for that type of stress, we can prevent these from happening down the road.

Before we begin with your action steps, let’s take a look at a little bit of the knee anatomy.

The Bones

Your knee joint consists of three main bones. You have:

- The tibia, which is your shin bone

- The femur, your thigh bone

- And the patella, a little triangular bone also known as the knee cap

- The fibula, which runs parallel to the tibia

The tibia and femur comprise one articulation of the knee, known as the tibiofemoral joint. An easy to way remember this is that the shin bone connects to the thigh bone.

In addition to that, there is the patellofemoral joint, where the patella connects to the femur.

The Ligaments

We’re only going to discuss the big guns here. Yes, there are more intricate parts of the knee (like the menisci and their associated ligaments) but for brevity, we’re going to leave them out. So that leaves us with:

- The cruciate ligaments— The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (ACL and PCL) stabilize the knee joint. The ACL keeps your tibia from sliding forward as well as your femur from sliding backward. The PCL does the exact opposite and keeps your tibia from sliding too far backward or your femur from going too far forward. They’re called “cruciate” ligaments because they cross each other

- The lateral collateral ligament— Also called the LCL, it connects to the head of your fibula and your femur. Like the ACL and PCL, it stabilizes the knee and helps keep your tibia from sliding too far laterally compared to your femur

- The medial collateral ligament— Known also as the MCL, it connects to the tibia and femur and prevents the tibia from sliding too far inward and helps protect you against valgus forces, while the LCL helps protect against varus forces

- Patellar ligament— Also called the patellar tendon, this is a continuation of the tendon found on your quadricep that connects to the patella. It goes over the patella and winds up connecting to your tibia

So the big picture is that your ligaments keep your knee stable while you do all the heavy lifting, walking, or running.

The Motions

At the knee joint, you’re capable of producing four different motions. They are as follows:

- Flexion—Bending of the knee. In the bottom of a deep squat or whenever you perform a hamstring curl, your knees are in flexion. Movements like the deadlift or good morning involve some knee flexion at the bottom, but not as much as in the squat or hamstring curl, and the hamstrings are the ones bringing your knee into flexion.

- Extension—Straightening of the knee. When you rise from a squat, deadlift, good morning, or you perform a knee extension, you are extending the knee. Your quadriceps are the main muscle group involved.

- Internal and external rotation—You can perform these while your knee is in flexion. In simple terms, you swivel inward or outward.

With respect to number three, these motions make it a bit more complex than your average hinge joint.

Application

In order to excel, you need to be able to perform these given motions well. For example, some can flex and extend their knee just fine. However, they might be lacking the ability to internally or externally rotate at the knee joint. The lack of use of your tissue in those general directions will create a problem if you ever need to move that way, or if you move that way on accident (maybe a misplaced step, or a stumble).

On the other hand, if your patella is out of line, you might notice that your tibia is either rotated either internally or externally. If you were to squat this way, your knees won’t track over your feet. If you don’t fix the problem, you could get injured. So we want to ensure that doesn’t happen.

The following exercises are going to help.

1. Hack Squat/Behind the Back Deadlift

This one is weird and not seen often. But, it’s a wonderful deadlift variation with a bit more focus on your quadriceps, in particular, the vastus medialis, which you might also know as “the tear drop.” The vastus medialis is important for proper tracking of your knee cap and direct stimulation of it will help strengthen the knee joint. This exercise happens to work it well and it doesn’t place a whole lot of direct stress on the knee joint.

When you perform this, you might feel like you are both leaning forward and reaching back with your shoulders. This is normal. For one, it will keep the bar from bumping into your calves and altering the groove. Two, if you have a big butt it won’t get in the way of the bar path.

If hip and back mobility are an issue, a simpler alternative is to do them from the rack at a height that you can handle.

2. Peterson Step-up

Another way to directly work the vastus medialis, this exercise can be done as a quad exercise unto itself, and it can also serve as a good warmup, or prehab movement. When performing, your shin is going to be at a closer angle to your foot than in a regular step-up as all the force is coming from the ball of your foot.

In addition to that, it’s not one that you want to use a heavy load with. Depending on your strength levels, a 20-30 pound dumbbell is a good start. To scale it up, try to increase the height of the step before you increase the weight.

Last, if you find yourself using your non working leg for help, try pointing it to the sky to prevent you from pushing off of it.

3. Tibia/Fibula Rotations

Executed with a resistance band, there are several ways you can go about this. If you are in the camp where you can’t articulate the movement without moving your hip as well, that’s fine. Start from there, practice the internal and external rotation that way, and refine it over time to where you can articulate just the tib/fib.

Next, you have the option of using the band to pull you in to a given rotation. As you can see in the video, the band is looped around your instep and you are moving from neutral to either internal or external rotation with the band’s assistance. If you can’t do the motion without the band, this is a good to help you get there.

Once you can perform the rotational movements of the tib/fib, you can strengthen the muscles that facilitate them (sartorious, popliteus, and gracilis) as well as the ligaments discussed earlier. To gain more movement and strength, you’ll do the opposite of what you have done before. You will use the band to provide resistance as you practice your rotations in either direction. If by some chance you happen to be hypermobile in this area, isometrics are a good alternative as well. All you do is keep the joint neutral, and resist the pull of the band.

Conclusion

While these aren’t the end all be all of knee health and strength, they will help. For the future of your knee health, start thinking about incorporating unilateral leg work as well. A good starting point is to focus on the other motions of your hips as well, like hip rotation and/or hip abduction. Not only that, for the exercises listed, don’t make them become the main thing you focus on. It doesn’t take much. A good example before your leg day would be to do 2-3×10 with the Peterson Step-up. Follow up with 2×10 of your banded tib/fib rotations. If you’re going the isometric route with the band work, opt for two sets of holds at 10-30 seconds. Then move on with your specific leg work, and see if you can notice better movement quality.