Once you have sufficient background knowledge in a given field of study, reading research is important. Knowledge is continuously growing, and staying on top of the research can help you develop a deeper and up-to-date understanding. However, reading research is quite different from reading a news article or a novel. It is a skill that can be learned, and this skill will serve as a lifelong tool to protect you from BS (we’ll say that stands for bad science).

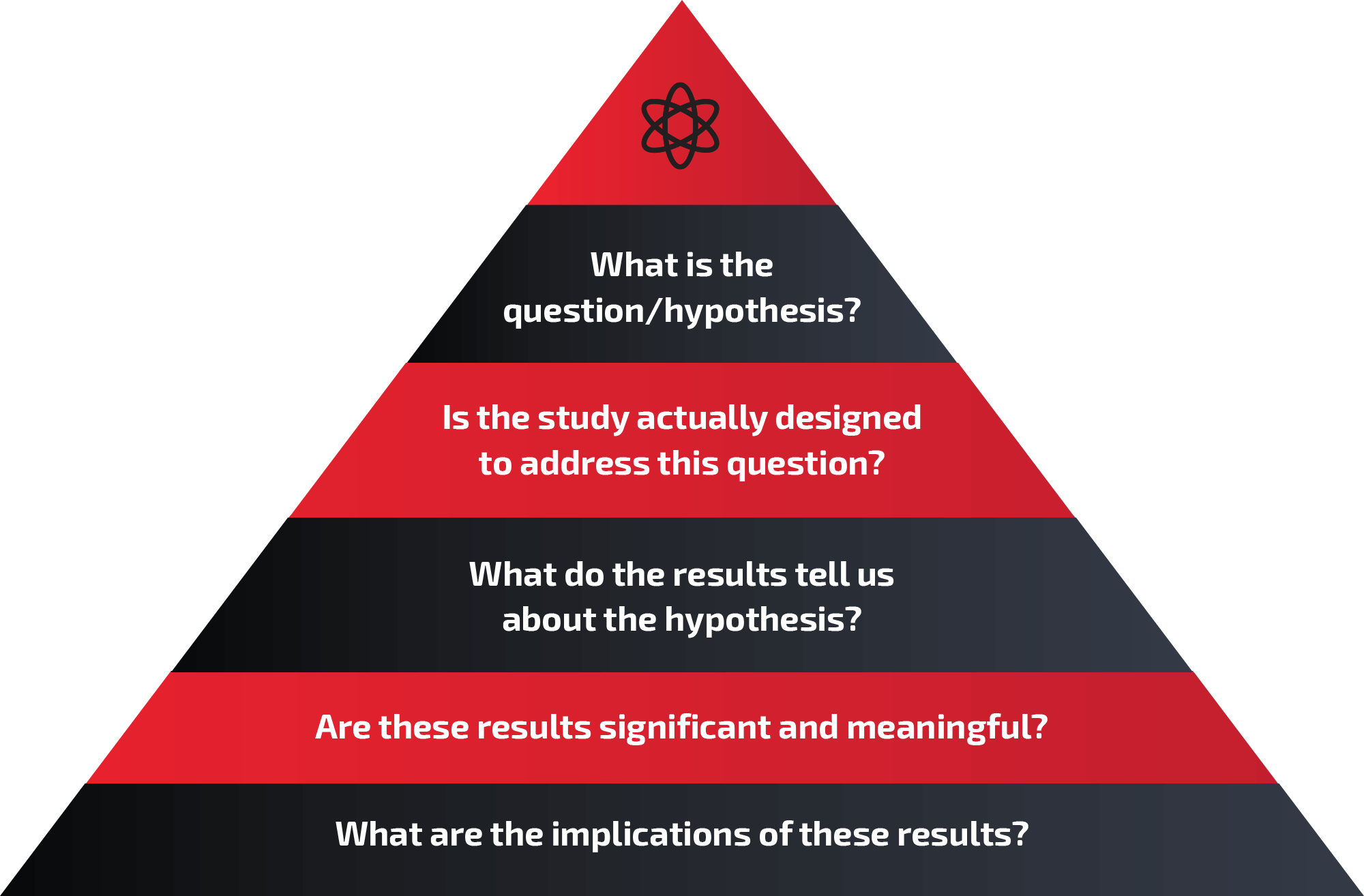

You can take entire college courses on how to read, interpret, and design research. I’m not smart enough to condense that much information into a single article, and I still have plenty of room to sharpen my own skills. Nonetheless, this article aims to walk you through the various sections of a peer-reviewed research paper, and provide a simple list of questions to ask yourself as you read each section. If you ask these questions as you work through a paper, they will assist you in interpreting what you read.

The sections

There is no “uniform” format for research journals. Some may omit certain sections, add extra sections, or combine sections. Nonetheless, we’ll assume a fairly common format for the purposes of this article, and take it section-by-section.

Abstract

This is basically the “Cliff’s Notes” of the paper. It will briefly tell you what the researchers intended to study, how they did it, and what they found. Word limits are extremely restrictive, so it’s impossible to evaluate a study based on its abstract. You simply can’t get a full understanding of how they carried out the study, which means you can’t interpret the results with a great deal of confidence. However, this section can provide helpful information if you ask yourself the following questions:

- What kind of paper is this?

- There are all kinds of papers, and some are inherently considered “stronger evidence” than others. If you’re reading a randomized controlled trial (RCT), meta-analysis, or systematic review, these are considered stronger levels of evidence. This doesn’t mean that other things, such as case studies or cross-sectional studies, shouldn’t be published; it just means that the design of a study will influence how broadly or confidently you can apply the findings.

- Am I interested enough to keep reading?

- The abstract is like a movie trailer. You get the genre, a general idea of the plot, and figure out who’s starring in it. Now you have to decide if you want to watch The Rock beat up bad guys for two hours. You can’t really tell if the movie is good or bad from the trailer, you just get an idea of what to expect.

Introduction/Background

This is where the authors “set the stage” for their study. They should provide a concise explanation of the topic at hand, and indicate what they hope to achieve with the study. It’s still entirely too early to determine the quality of the paper, but you can ask the following questions:

- Do they know what they’re talking about?

- You might occasionally find an introduction in which the authors don’t seem to have a very firm (or unbiased) grasp on the paper topic. This is obviously a red flag when evaluating how well the study might have been conducted.

- Is their research question worth addressing?

- If the paper got published in a decent journal, that means at least a couple of peers in their field felt the paper was worth publishing. But you might find that the paper doesn’t address questions that you are interested in. If the authors are attempting to answer a set of questions that aren’t worth your time, you may choose to stop reading altogether.

- What is their purpose and hypothesis?

- By the end of the introduction, you should be able to figure out the purpose of the paper and imply what the authors expected to find. It’s important to find this information, as it will help you evaluate if the methods are appropriate for achieving this purpose.

Methods

This is the “meat” of the paper, and where most of the evaluation process takes place. Authors will describe what they measured, how they measured it, who the subjects were, and how the statistical analyses were performed. The following questions come in handy while reading the methods:

- What kind of subjects did they use?

- Always consider how the type of subject relates to the outcomes that are measured. Human vs. animal model, male vs. female, young vs. elderly, sedentary vs. well-trained. For example, if you based your protein needs on a study conducted in the elderly, it’d be important to recognize that elderly individuals display a blunted anabolic response to dietary protein. If something caused robust strength gains in totally untrained people, the results in well-trained athletes would likely be less extreme. Always consider how the findings might be influenced by the type of subjects used.

- Does the overall design make sense?

- Is the general timeline of the study appropriate (i.e. the duration of the study, when things were measured, washout periods, etc.)? Have groups been assigned appropriately? Have they effectively controlled for confounding variables that might mess up the results? It takes a little bit of background information to determine if the study is well designed, but these factors are important to consider. A study will struggle to adequately answer the research question if the design is flawed from the start.

- Were the measurements appropriate?

- If you’re doing a one week weight loss study, DXA or BodPod probably won’t be sensitive enough to detect real differences in body composition. The measurements selected should be relevant to the research question, validated for what they intend to measure, and sensitive and reliable enough to detect the changes you anticipate. In most cases, authors should provide plenty of detail about exactly how their measurements were taken. It’s always helpful to keep a watchful eye over how they performed various tests or measurements, as incorrect procedures can make a huge difference.

- Were the stats appropriate?

- A thorough explanation of statistical procedures is way beyond the scope of this article. Ideally, reviewers will thoroughly address this in the review process. But if you have a background in statistics, this is one of the most important questions you can ask when reviewing the methods!

Results

This section should be pretty straightforward. The results of any statistical analyses should be presented, but most journals discourage authors from interpreting those results in this section. The primary questions you should ask yourself are:

- Were the findings statistically significant?

- This generally boils down to the p-values reported for each outcome. If the p-value is less than or equal to 0.05, that is generally considered a statistically significant finding. This can loosely translate to the authors saying, “There is less than a five percent chance that these findings could be explained by random chance, so we’re feeling pretty confident.”

- Were the “significant” findings actually meaningful?

- This is the far more subjective question. A low p-value is not necessarily an important finding. For example, did you find a “significant” change of 1% body fat, but use a measuring device with a measurement error of 3%? If so, this change could easily be attributed to measurement error. Similarly, imagine that a one-year study found a “significant” weight loss of 1.1 pounds. That’s fine, but no reason to let everyone know that we found the solution to the obesity epidemic.

- This issue also goes the other direction sometimes- you might see a change or difference that looks meaningful, but is not statistically significant. As an athlete or practitioner, you might be sufficiently convinced that this observation is “real” and could be useful to you or your clients. That’s fine, but don’t try to convince your statistics professor that it’s meaningful.

- Do the results make sense? Could something else explain the findings?

- If you study a supplement and report muscle gains that are 10 times higher than every other study on the ingredient, I will naturally be skeptical. Sometimes findings are “too good to be true” (or unexpectedly “bad”), and receive well-deserved skepticism. The presence of an uncontrolled confounding variable can also raise significant questions about the validity of the results.

Discussion/Conclusion

These sections are where authors will relate their findings to previous work, discuss the overall impact of their findings, note their limitations, and formulate some conclusions. The following questions are helpful in guiding your interpretation:

- Do authors acknowledge their limitations and address “alternative” explanations?

- In most studies, authors will present an explanation for “why” their findings were observed. Always consider alternative explanations. For example, imagine that Group A increases strength more than Group B in a study. Could it be because Group A was weaker than B at the start, or because Group A’s training program was more similar to the performance tests that were used to measure strength? Authors should acknowledge all of the limitations of their study, and should also work to calm the reader’s concerns about relevant “alternative” explanations. If the authors fail to address alternative explanations, you might have reason to question their conclusions.

- Does the discussion actually match their results? Are they “reaching?”

- Authors will sometimes talk up their results to seem a bit more impressive or important than they really are. Reviewers usually catch this and tell them to tone it down, but it sometimes slips through nonetheless. The important thing is, don’t take the authors’ word for it. Their discussion or conclusion might make it sound like they changed the world, but you can always check the results section to see how justified their statements are.

- How can I apply this information?

- This is probably the main reason you are reading research in the first place. After evaluating the quality of the paper based on the previously listed questions, the discussion section and conclusions should help you determine if, and how, these results may apply to you or your clients.

What about the funding source?

Researchers will identify the funding source(s) for their project. There’s nothing wrong with taking a look to see who funded a study, but I encourage readers to hesitate before immediately assuming corruption. The reality is that research costs money, and research is frequently funded by groups that have some sort of interest in the topic. Consider this- if a group had absolutely nothing to do with creatine, why would they bother funding creatine research? Skepticism will always be present with industry-funded research, but I’m not quite cynical enough to assume that a large number of researchers are willing to sacrifice their morals and reputation for what is usually (in our field) a pretty modest grant.

Conclusion

As you read through a research paper, these types of questions should help guide you toward a fair but critical interpretation of what you’re reading. You should always read with a critical, skeptical eye, but don’t be entirely unrealistic. Remember that research is conducted by human beings with limited time and resources, and that the subjects are often human beings as well. So find that middle ground between gullible and excessively skeptical, find an interesting paper, and start building your research interpretation skills!